Shoulder Anatomy Guide - A Physiotherapist’s Guide to the Anatomy Behind Common Conditions

The shoulder is one of the most versatile yet complex regions of the body — built for both strength and mobility. This page explores the anatomy of the shoulder, including its bones, joints, ligaments, muscles, tendons, nerves, and vascular structures, and how these components work together to provide stability and movement.

As this page develops, new internal links will connect directly to related articles linking this anatomy to some of the most common shoulder conditions, such as rotator cuff tears, supraspinatus injuries, shoulder impingement syndromes, and bursitis — all helping you understand both the structure and the clinical relevance of each area.Whether you’re learning anatomy, recovering from injury, or simply curious about how the shoulder works, this evolving resource aims to make expert knowledge clear, accurate, and accessible.

Condition Related Articles

- Spinal Anatomy?

- Spinal Stenosis

- Sciatica

- Prolapsed Disc

Get WISE - Get WELL - Get ON

Bones of the Shoulder

The shoulder is a complex ball-and-socket joint comprising three primary bones: the humerus, scapula, and clavicle.

The Humerus (Upper Arm Bone)

The top end of the humerus forms the ball of the shoulder joint. This ball-like structure fits into the glenoid cavity of the scapula, allowing for a wide range of motion. The humerus is crucial for all arm movements, and any injury to this bone can significantly impact mobility and function.

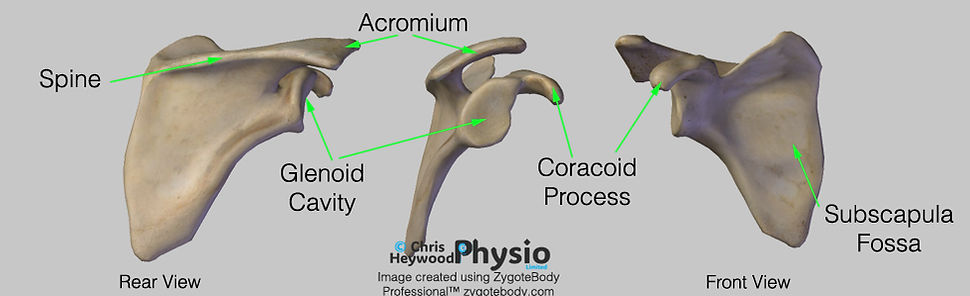

The Scapula (Shoulder Blade): Anchor for Shoulder Movement and Stability

The scapula, or shoulder blade, is a flat, triangular bone that forms the posterior (back) part of the shoulder girdle. It acts as a crucial anchor for many muscles and ligaments that support shoulder stability, mobility, and arm function. Several of the rotator cuff muscles — including the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis, and teres minor — all originate from specific surfaces of the scapula.

These muscles are commonly involved in shoulder injuries and can explore these in more detail on the rotator cuff tear page.

Key Bony Landmarks of the Scapula:

Acromion:

A bony projection that extends over the shoulder joint and connects with the clavicle to form the acromioclavicular (AC) joint. It provides protection to the underlying rotator cuff tendons, particularly the supraspinatus, and serves as a site of deltoid muscle attachment.

Spine of the Scapula:

A prominent ridge that runs across the back of the scapula, dividing it into the supraspinous fossa (above the spine) and infraspinous fossa (below the spine). These fossae serve as the origin points for the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles, respectively.

Subscapular Fossa

The subscapular fossa is a broad, slightly concave surface on the anterior (front) aspect of the scapula. It serves as the origin site for the subscapularis muscle, which is the largest and strongest of the rotator cuff muscles. This fossa provides a smooth area for the muscle to lie against the rib cage, allowing efficient gliding during shoulder movement. Because of its location and relationship to the thoracic wall, the subscapular fossa is not externally visible but plays a vital role in shoulder function and stability.

Coracoid Process:

A hook-like structure on the front of the scapula. It serves as an attachment point for several ligaments and muscles, including the short head of the biceps, coracobrachialis, and pectoralis minor. It also lies near the subscapularis, which originates from the anterior surface of the scapula.

Glenoid Cavity (or glenoid fossa):

A shallow, cup-like socket that articulates with the head of the humerus to form the glenohumeral joint. This joint is stabilised by the surrounding rotator cuff muscles, all of which help keep the humeral head centred during movement.

Clavicle (Collar Bone)

The S-shaped clavicle connects the scapula to the sternum, forming the acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joints. It also protects vital nerves and blood vessels passing from the spine to the arms. The clavicle acts as a strut, maintaining the shoulder blade in a position where it can function effectively.

The articulating bones are cushioned by articular cartilage, which minimises friction and acts as a shock absorber. This smooth, white tissue covers the ends of the bones, allowing them to glide over each other without causing damage.

Additionally, the glenoid labrum, a ring of fibrous cartilage, enhances the glenoid cavity’s depth and surface area, securing the humeral head more effectively. The labrum acts like a suction cup to hold the ball of the joint in place, adding an extra layer of stability.

Soft Tissues in the Shoulder

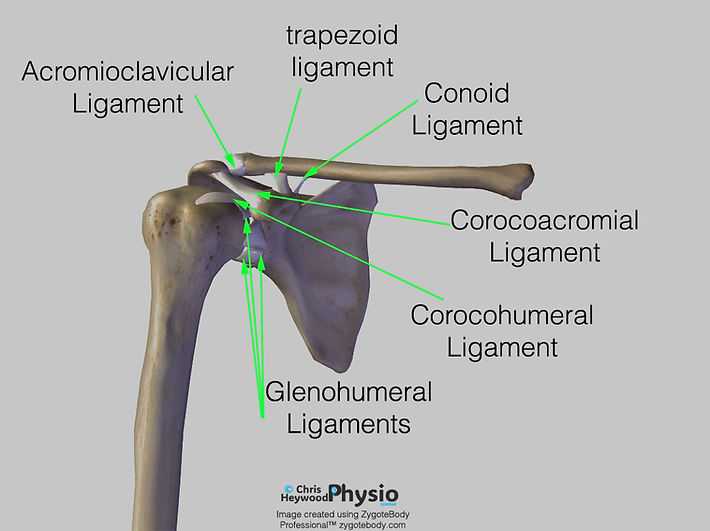

Shoulder Ligaments

A ligament is a strong, flexible band of connective tissue that connects one bone to another. It helps stabilise joints, guide normal movement, and prevent excessive motion that could cause injury. In the shoulder, ligaments keep the bones aligned while still allowing a wide range of movement.

Coracoclavicular Ligaments

This ligament forms an arch over the shoulder joint, protecting the humeral head and rotator cuff tendons from direct trauma.

Acromioclavicular Ligaments

This ligament strengthens the acromioclavicular joint, helping to maintain the alignment of the clavicle and the scapula.

Coracoacromial Ligaments

These ligaments are essential for stabilising the clavicle and preventing dislocation of the acromioclavicular joint. They consist of two parts: the conoid and trapezoid ligaments.

Glenohumeral Ligaments

A set of three ligaments (superior, middle, and inferior) that form a capsule around the shoulder joint, preventing dislocation and ensuring stability. These ligaments are critical in maintaining the shoulder’s range of motion while preventing excessive movement that could lead to injury.

Summary

Shoulder Muscles and Tendons

The rotator cuff, consisting of four muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis), forms a sleeve around the shoulder joint, providing stability and facilitating movement. These muscles work together to keep the humeral head cantered in the glenoid cavity during arm movements.

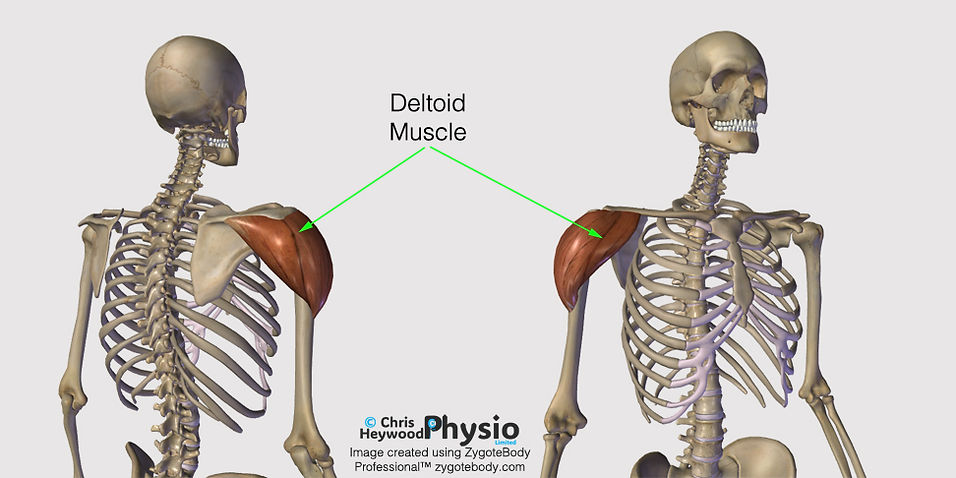

Deltoid Muscle

The deltoid, the largest and strongest muscle in the shoulder, covers the rotator cuff and is responsible for lifting the arm and giving the shoulder its rounded shape. It plays a vital role in abduction, flexion, and extension of the shoulder.

Biceps Tendons

Two tendons (long head and short head) connect the bicep muscle to the shoulder, allowing for flexion and supination of the forearm.

Rotator Cuff

These four tendons (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis) attach the humerus to the rotator cuff muscles, ensuring stability and mobility. They are crucial for maintaining shoulder stability during dynamic movements.

Major Nerves of the Shoulder and Arm

Nerves, which transmit signals between the brain and muscles, pass through the shoulder from the neck, forming the brachial plexus. This network of nerves controls muscle movements and sensations in the shoulder, arm, and hand.

The Brachial Plexus

The brachial plexus he brachial plexus is a network of nerves that originates from the spinal cord in the neck (C5 to T1 nerve roots). Globally it supplies the shoulder, arm, forearm, and hand with motor and sensory innervation. It branches into several major nerves, including the musculocutaneous, axillary, radial, ulnar, and median nerves, which innervate different parts of the arm and hand.

Major Blood Vessels of the Shoulder and Arm

Arteries

Oxygenated blood is supplied to the shoulder region by the subclavian artery, which becomes the axillary artery in the armpit and the brachial artery down the arm. These arteries ensure that muscles receive the oxygen and nutrients needed for optimal function.

Veins

veins include the axillary vein, which drains into the subclavian vein; the cephalic vein, which runs along the upper arm; and the basilic vein, located near the triceps muscle. These veins are responsible for returning de-oxygenated blood to the heart for purification.

Shoulder Anatomy Summary

Understanding the anatomy of the shoulder helps explain why certain injuries occur and why accurate assessment matters. The joint’s remarkable range of motion depends on the coordinated function of the rotator cuff tendons, ligaments, and surrounding muscles, as well as the nerves and blood vessels that supply them. When one of these structures becomes irritated or damaged — as in impingement syndromes, bursitis, or rotator cuff tears — even small movements can become painful or restricted.

As a physiotherapist in Northampton, I use a detailed understanding of these structures to guide treatment, whether through manual therapy, sports massage, or targeted rehabilitation exercises. This anatomical knowledge allows each session to be precise, efficient, and focused on long-term recovery rather than short-term fixes.

If you’re struggling with shoulder pain or recovering from injury, professional assessment can make all the difference. You can book an appointment directly for a one-to-one consultation — or simply explore the educational pages linked here to better understand your condition.

And if you’ve found this information helpful, please feel free to share this page with anyone who might benefit. Helping people understand their bodies is the first step toward helping them move well again.

Shoulder Anatomy FAQ's

1) What are the main bones that make up the shoulder?

The shoulder is formed by three main bones — the humerus (upper arm bone), scapula (shoulder blade), and clavicle (collarbone). Together they create a ball-and-socket joint that allows a large range of motion.

2) What are the main bones that make up the shoulder?

The rotator cuff is a group of four muscles and their tendons — supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis. They work together to stabilise the shoulder and control movement of the arm.

3) Why is the shoulder joint so flexible?

The shoulder joint’s ball-and-socket design gives it exceptional mobility. The “socket” (glenoid) is relatively shallow, allowing the arm to move freely — but this also makes the joint more prone to instability and injury.

4) What are the main ligaments in the shoulder?

Key ligaments include the glenohumeral ligaments (which stabilise the ball in the socket), the coracoclavicular ligament (linking the clavicle to the scapula), and the acromioclavicular ligament (supporting the joint at the top of the shoulder).

5) What is the labrum and what does it do?

The labrum is a ring of cartilage that deepens the shoulder socket, improving stability and cushioning. Tears of the labrum are common in athletes or those who’ve had shoulder dislocations.

6) What role does the scapula play in shoulder movement?

The scapula (shoulder blade) acts as a stable base for shoulder motion. Muscles attached to it — like the trapezius, serratus anterior, and rhomboids — coordinate arm movement and maintain posture.

7) What is the acromioclavicular (AC) joint?

The AC joint sits at the top of the shoulder where the clavicle meets the acromion (part of the scapula). It helps transfer load from the arm to the rest of the skeleton and is often involved in “shoulder separation” injuries.

8) How does the shoulder achieve such a wide range of movement?

The shoulder’s mobility comes from the coordinated motion of several joints — the glenohumeral, AC, sternoclavicular, and scapulothoracic joints. Muscles around the shoulder blade and chest wall also contribute to smooth, efficient movement.

9) Why does the shoulder commonly dislocate?

Because the shoulder’s socket is shallow, stability relies heavily on soft tissues (muscles, tendons, and ligaments). A strong force or awkward fall can push the ball (humeral head) out of the socket — a dislocation.

10) What are common structures involved in shoulder pain?

Common pain sources include the rotator cuff tendons, bursa (fluid-filled sacs that reduce friction), the AC joint, and the labrum. Pain may also be referred from the neck or upper back.

Why You Should Choose Chris Heywood Physio

The most important thing when seeking help is finding a practitioner you trust—someone who is honest, responsible, and clear about your diagnosis, the treatment you really need, and whether any follow-up appointments are necessary.

I’m not here to poach you from another therapist, but if you’re looking for a new physiotherapist in Northamptonshire or simply want a second opinion, here’s why many people choose to work with me (read my reviews):

Over 25 Years of Experience & Proven Expertise

With 25+ years of hands-on physiotherapy experience, I’ve built a trusted reputation for clinical excellence and evidence-based care. My approach combines proven techniques with the latest research, so you can feel confident you’re in safe, skilled hands.

Longer Appointments for Better Results

No two people—or injuries—are the same. That’s why I offer 60-minute one-to-one sessions, giving us time to:

-

Thoroughly assess your condition

-

Provide focused, effective treatment

-

Explain what’s really going on in a clear, simple way

Your treatment plan is tailored specifically to you, aiming for long-term results, not just temporary relief.

Honest Advice & Support You Can Trust

I’ll always tell you what’s best for you—even if that means you need fewer sessions, not more. My goal is your recovery and wellbeing, not keeping you coming back unnecessarily. I have low overheads nowadays and I do not have pre-set management targets to maximise patient 'average session per condition' (yes it does happen commonly and I hate it with a passion - read my article here)

Helping You Take Control of Your Recovery

I believe the best outcomes happen when you understand your body. I’ll explain your condition clearly, give you practical tools for self-management, and step in with expert hands-on treatment when it’s genuinely needed.

Looking for a physiotherapist who values honesty, expertise, and your long-term health?

Book an appointment today and take the first step towards feeling better.

Contact Info

On a Monday and Tuesday I work as a advance musculoskeletal specialist in primary care but I can still be contacted for enquiries. You are welcome to call but it is often faster for me to reply via an email or watsapp message, simply as my phone will be on silent in clinic. Either way, I will reply as soon as possible, which in the week, is almost always on the same day at the latest.

Clinic Opening Hours

** Please note that online sessions and Aquatic sessions be arranged outside of normal clinical hours on request.**

Sat -Sun

Closed

0900 - 1330

Closed - First Contact Practitioner Work

Weds - Fri

Mon - Tues